In the spring of 1945, 100 Chinese officers were carefully selected for a highly classified special assignment. On April 14, 1945, they were ordered to board a plane bound for the US. The nature of their top secret assignment was not disclosed. They later came to be known as the FAB-100.

The members of the FAB-100 were all young officers and some were recent college graduates. Many had been enrolled in the Chinese Southwest Associated University, which had been set up by the Nationalist Chinese to continue the education of students displaced from their home universities in Beijing and Nanjing during the Japanese occupation. Each officer was fluent in English and well-versed in American Military doctrine. Many had seen heavy combat.Up until their departure for the US, their unit was positioned directly under the headquarters of the Chinese National Central Military Commission in Chungking (the US War Department’s counterpart).

Their departure from China was clandestine. In the first leg of their journey, they were flown in C-47 Dakotas to Ledo (Burma, modern-day Myannmar) and over the Himalayan peaks into Karachi (then a part of India), where they transferred to C-54s. The second leg of thier journey took them Saudi Arabia, Cairo, Libya, Casablanca, the Azores and then on to Newfoundland. The trip did not allow for any layovers at the numerous refueling stops to preclude tipping off Axis agents that the Chinese officers were hurrying westward to the United States.

“The mission priority was so high that we flew into and around weather that would have grounded other aircraft,” explained Tommy Cheng, one of the FAB-100.[1]

So highly classified was their mission, that US general officers in New York were unaware of the Chinese officers’ arrival.

The group of 100 arrived in two separate subgroups:

The first 50 left Kunming, China (home of the American volunteer group, the “Flying Tigers”) on April 17, 1945, arriving at LaGuardia Marine Air Terminal in New York on April 21, 1945. Their next stop was the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center at Randolph Field, texas, where they lived in isolation until new orders arrived from Washington.

The second group left Kunming on June 19, 1945, arriving on June 24. They were sent to Minter Air Field in Bakersfield, CA.

place your mouse cursor over picture to see names on the flip side of this photo!

The 2nd batch of FAB personnel serving in USA • Minter Field, Bakersfield, CA • July 13, 1945. Photo shows 49 of the 100 officers, courtesy of David Sze—published by permission.

While in China, the young officers had been doing interpretion and translation work for members of the American Army Liaison teams who worked with their counterparts in the Chinese Ground Force. In the words of former FAB-100 member S. L. Wang, “we learned how to lob grenades ourselves, then turned around and showed the recruit[s] how to cock [their] elbow[s]. We learned how to read the ‘T/O’s (Tables of Organization) and were called upon to interpret and even mediate between the Chinese and American generals across the table.”[2]

When they arrived in the US, they found the work to be more structured and often less intense. They interpreted and translated for American instructors and Chinese Air Force cadets, occasionally becoming the instructors themselves. They worked in classrooms, labs and shops, on the flight line and sometimes in the air. They came to be known as the “Chinese Detachment” or “Chinese Training Detachment” and were involved in the specialist training of aviation mechanics, bombardiers, meteorologists, navigators, pilots, radio mechanics and radio operators, eventually serving at most major air bases in the South, Midwest and Western US. [2]

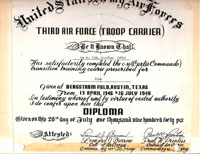

From September of 1945 to the Summer of 1946, members of the Chinese Detachment were stationed at Bergstrom Army Air Field.

“We went there after V.J. Day and stayed until the entire Chinese Air Force Training Program came to an end in the early summer of 1946,” Eugene Wu, former chief interpreter explains. “We took over the entire Bergstrom Field at that time and were known as the ‘Chinese Training Detachment.’”

According to the Austin American-Statesman, on July 19, 1946, “the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing, with [its] headquarters at Bergstrom Field, was charged with the supervision of the operations program and the base personnel assumed the problems of housing, feeding and providing recreational facilities for the trainees.

“The Chinese soldier students were accompanied by civilian interpreters from the Chinese Foreign Affairs Bureau, who were assigned the work of translating eight training manuals totaling 1,400 pages. Other school projects included the painstaking dubbing of Chinese for the sound tracks of training films used in the various courses.”

The FAB-100 never carried out its original secret mission and the true purpose of their recruitment has never been revealed. Their US ID papers officially listed them as “Experts” employed by the War Department. Historians have surmised that they were part of an Allied plan to open a second front on the Chinese mainland prior to landing in Japan, in order to draw off the Japanese troops from the homeland defense. However, Japan’s unconditional surrender rendered this plan moot.

The FAB-100 were officially disbanded in December 1945, but did not receive their discharge from the Chinese Army until September 1946. The officers were then given the option of returning to China or remaining in the United States. Of the 100, 56 chose to stay in the US and continue their education, many receiving advanced degrees.

President Truman awarded 22 of the FAB-100 the Presidential Medal of Freedom for “meritorious service which has aided the United States in the prosecution of a war against an enemy.”

It took more than 50 years for some of them to receive their medals and a few are yet to obtain theirs. Six of 13 surviving members of the FAB-100 were reunited at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport in 2006 to receive their honors.

The Austin Chronicle Aug. 4, 2006:

“In 1945, Robert Chin was one of 100 Chinese military officers flown to the U.S. to serve as interpreters for Chinese pilots training for a top-secret World War II mission against Japan. The FAB-100, as they were known, were scattered at military bases across America, including what was then Bergstrom Army Air Field in Austin. On Sunday, Chin and five other surviving members of the Bergstrom group reunited at their old base – now Austin-Bergstrom International Airport – to mark the unveiling of a display honoring their largely forgotten role in America's and Austin's history. Although the war's end cut short the FAB-100 mission, members were nonetheless given the Medal of Freedom by President Truman, and many stayed in the United States. One of the event sponsors was Larry Tu, senior vice-president and general counsel of Dell Inc. and son of the late Duke Tu, a FAB-100 member.—

Bob Robuck, News 8 Austin, Jul. 31, 2006:

Six Chinese military officers finally came back to Austin to receive honors for their

bravery during World War II. The six were members of the elite FAB-100, officers brought over from China in 1945 to serve as interpreters for Chinese pilots. The United States worked to train the pilots for a top secret mission.

“I think the top secret part was before we came down to train the cadets. I think they had something else in mind for us to do,” FAB-100 member Tommy Cheng said.

To this day, nobody knows what that something was. The U.S. military stationed officers across the nation for the classified project. The six are all that remain of those at Bergstom Air Force Base, which is now the city's airport.

When the officers arrived back in Austin, they were overwhelmed.

“Going to a totally new country, you have no knowledge of it, no understanding of it except in a very vague sense, particularly during war time. A lot of it was hush-hush,” FAB-100 member Eugene Wu said.

The end of the war cut their project short. The bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and the FAB-100 mission was all but forgotten. But this weekend Austin city leaders remembered the men and honored their efforts at a special ceremony at the Airport Hilton. A permanent exhibit of the FAB-100 now stands inside the airport as a testament to their bravery. Members of the FAB-100 received Medals of Freedom from President Harry S. Truman following the war.

FAB-100 EXHIBIT, Austin Bergstrom International Airport:

The FAB-100 were officers from the Chinese Military who served as interpreters for the U.S. at the end of World War II, some of them stationed here in Austin at the Bergstrom Army Air Field. Six of the original 100 men are in town today to help celebrate the grand unveiling of a new permanent display at the airport commemorating their heroic efforts, and the ceremony will be officiated by Mayor Pro Tem Betty Dunkerley and Houston's Chinese Consul General Hua Jinshou.

MEDIA ADVISORY, Bergstrom Austin Community Council:

SIX FAB-100 MEDAL OF FREEDOM RECIPIENTS WILLATTEND DEDICATION CEREMONY OF EXHIBIT IN THEIR HONOR.

Austin, TX — Six of the 13 living FAB-100 Medal of Freedom recipients will be in Austin for the July 30, 2006 dedication of an exhibit that honors the story of their top-secret mission to the United States in 1945. Of the six attending the ceremony and reception following, three were stationed at Bergstrom Army Air Field.

Dedication/Reception details:

When: Sunday, July 30, 2006 at 1:00 pm

Where: Dedication will take place at the Bergstrom AFB Memorial display located in the ticket terminal of Austin-Bergstrom International Airport (across from the Jet Blue ticket counter.) The reception will follow at 2:00 p.m. in the Hilton Austin Airport and is by invitation.

The story of the FAB-100 is attached to this advisory. The gentlemen who will be attending the dedication and reception are:

- Tommy Cheng (from Fairfield, CA — stationed at Bergstrom);

- Robert Chin (El Cerrito, CA);

- Hai C. Tan (Hacienda Heights, CA);

- Joseph Tso (Napanoch, NY—stationed at Bergstrom);

- S. L. Wang (Cortland Manor, NY—stationed at Randolph Field, San Antonio);

- and Eugene Wu (Menlo Park, CA — stationed at Bergstrom).

Personnel from ABIA will be conducing a tour of the airport property for the FAB-100 prior to the dedication. Arrangements for interviews other than at the dedication or reception may be made by calling Kathy Pillmore at 512-292-1194.

In addition to the FAB-100 members, guests invited to speak at the dedication include: Mayor Will Wynn; Mr. Hua Jinshou, the Consul General of the People’s Republic of China, Houston Consulate; Ms. Amy Mok, President & CEO of the Asian-American Cultural Center; and Mr. Larry Tu, Sr. Vice President and General Counsel of Dell, Inc. who’s father, now deceased, was a member of the FAB-100

FAB-100 Dedication and Reception July 19, 2006

The Bergstrom-Austin Community Council was formed in the 1950s by members of the Austin business community who saw the need for an organization that would represent the civilian community in support of the men and women at Bergstrom Air Force Base. From the beginning, the goal was to form a bond and partnership between the Air Force and Austin.

With the closure of Bergstrom Air Force Base, the BACC members gathered the funds to create the memorial to the history of the base that currently resides in the ABIA ticket terminal. The memorial is a chronology of Bergstrom from its formation in 1941 to the departure of the last units in 1997. The memorial is funded through private donations.

The Story of the FAB-100

In the Spring of 1945 the war in Europe had ended, but the battle in the Pacific raged on. One hundred Chinese officers attached to China’s Foreign Affairs Bureau were chosen for a top-secret mission that would find them in the service of the US War Department.

All of the officers were college graduates and spoke fluent English. In China they interpreted and translated as members of the American Army Liaison teams working with their counterparts in the Chinese Ground Force. Some had seen battle on the front lines and in campaigns in Western Yunnan Province and Burma. They would use their experience in America interpreting for Chinese pilots who were being trained for a mission against Japan.

The FAB-100 left Kunming, China (home of the American Flying Tigers) in two groups of 50. The first group departed April 17, 1945 in three C-46 cargo planes. The Pacific route was closed to non-combat flights so they took a more circuitous route by way of India, Africa and the Atlantic. They refueled in Myitkyina, Agara (Agra), New Delhi, Karachi, Abadan, Cairo, Tripoli, the Azores and Newfoundland and eventually arrived at LaGuardia Marine Air Terminal in New York on April 21, 1945. Their next stop was the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center where they lived in isolation until new orders arrived from Washington. The second group of 50 left Kunming in three planes on June 19, 1945. Two planes landed in New York on June 24 and one was diverted to Washington D. C. because of foul weather. Their next stop was Minter Air Field in Bakersfield, California.

According to news accounts, “the FAB-100 orders allowed for no layover at any of the fueling stops to preclude tipping off the Axis agents that Chinese officers were hurrying westward to the United States. Their mission was of such a priority that they flew through weather that would have grounded other aircraft. So highly classified was the FAB-100 journey, that general officers in New York were unaware of the officers’ arrival.”[3]

Once at their destinations, the interpreters translated for American instructors and the Chinese Air Force cadets. They worked in the classrooms, labs and shops, on the flight line and sometimes in the air. They covered specialty training for aviation mechanics, bombardiers, meteorologists, navigators, pilots and radio mechanics and operators. They were stationed at most of the major air bases in the south, Midwest and western states.

Those stationed at Bergstrom Army Air Field helped to train troop carrier pilots and crews. Instructors from the 349th Troop Carrier Group and their students were commended for a job well done by Col. James E.. Duke, Jr., commanding officer of Bergstrom Field. “Considering the language difficulties and the limited time in which the C46 transition school had to be organized, the program has been an outstanding success.”[4]

Their graduation was slated for July 31, 1946 and the Statesman noted that the date “will formally mark the end of their training, with graduation exercises to be attended by dignitaries and officials from all parts of the country and from their homeland. On that day, and on the day following…Bergstrom Field will hold open house in a two-day program commemorating the graduation and National Air Forces Day, respectively.”

The true nature of the mission of the FAB-100 and their pilot counterparts was never revealed; however, historians have surmised that the Allies planned to open a second front on the Chinese mainland prior to landing in Japan in order to draw off Japanese troops from the homeland defense. The plan might also have called for the Allies to trap the large contingent of Japanese troops already on the Chinese mainland and deny use of these troops for homeland defense.

With the surrender of the Japanese on September 2, 1945, the mission of the FAB-100 was ended. They were officially disbanded in January, 1946 and were given the option to return to China or remain in the United States under the condition that they continue their college education. Fifty-six chose to stay, and many acquired advanced degrees.

In July of 1945, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order No. 9586 instituting the Medal of Freedom in order to recognize foreigners who assisted in the US military operations. Twenty-two of the members of the FAB-100 were awarded Medals of Freedom; however, it took almost 50 years for the medals to get into the hands of the recipients.

Portions of the FAB-100 story were extracted from the FAB-100 Commemorative Album written by S. L. Wang, FAB-100 member

COMMITTEEBRIDGES Newsletter FALL 06:

Larry Tu moved to Austin, Texas two years ago when he became Senior Vice President, General Counsel and Board Secretary for Dell Inc. To his surprise, he learned that his family’s Austin roots went back sixty years. During World War II, his late father was stationed at Austin’s Bergstrom Army Air Field, one of a select group of 100 military officers attached to the Chinese Foreign Affairs Bureau who had been sent to the U.S. to train for a joint Chinese-American secret mission which was to have been carried out in 1946. It was Tu’s idea to commemorate the FAB-100, as the group was known, with a display and ceremony at what is now the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport. Attending the July 30 commemoration were six of the surviving FAB- 100, many of whom stayed in the U.S. after the war ended in 1945, along with American WWII veterans who had fought alongside Chinese forces, Austin’s Chinese community, and the Austin City Council. Tu and his wife Betsy Ashcraft were among the speakers at the ceremony, as was Chinese Consul General Hua Jinshou. Tu initiated this project because “in this time when U.S.-China relations can become tense and politicized, it’s good to remind ourselves of the connections people make at the individual level and reaffirm the diversity and inclusiveness that are the hallmarks of this country.”

MEL BROWN, Author:

Chinese Americans

I was interviewed for “KLRU Presents: The World, The War and Texas” to discuss Texas Chinese Americans who served during World War II, as a lead-in to Ken Burns “The War.” I am the author of a book on the contributions of Chinese Americans to Texas.

The KLRU film contains no mention of Chinese American servicemen. I donated several photos of, and was taped for nearly an hour talking about, Chinese American airmen who served with the U.S. Air Force’s 14th Air Service Group. I discussed Sgt. Wayne Lim, winner of the Distinguished Flying Cross as a B-24 tail gunner who flew 35 missions over Europe.

KLRU featured the FAB-100 instead. They were mainland Chinese Air Force officers who trained at Bergstrom Army Air Field. Japan surrendered before they could deploy.

KLRU’s honoring of foreign nationals while ignoring the sacrifice of local Chinese Americans was wrong.

MEL BROWN

melbjr@earthlink.net

Austin

LIST OF KNOWN OFFICERS:

- Duke Tu [www.asianaustin.com/news/show/69 — Last accessed: Jul. 2009]

- Eugene Wu [www.news8austin.com/content/top_stories/default.asp?ArID=167711 Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- Hai C. Tan [www.committee100.org/events/links/upcoming/fab100_pressrelease.pdf Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- Joseph Tso [www.committee100.org/events/links/upcoming/fab100_pressrelease.pdf Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- Robert Chin [www.austinchronicle.com/gyrobase/Issue/story?oid=oid%3A392313 Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- S. L. Wang [www.committee100.org/events/links/upcoming/fab100_pressrelease.pdf Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- Tommy Cheng [www.news8austin.com/content/top_stories/default.asp?ArID=167711 Last accessed: Jul 2009]

- Eugene Wu — in charge of first batch of 50 officers who departed for the USA in April 1945

- Pieh Chin-Tien (1919-1954) — opted to leave US for Taiwan

- Alan Lan Pan (1923-2001) (see above, Officer #54 ) — from Guizhou province

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

- The family of Pieh Chin-Tien

- David Sze

- My late father, whose exploits in WW2 first sparked my interest

WEB REFERENCES:

- www.caspa-austin.com/pdf/FAB-100_Narrative.doc [Last accessed: Jul. 2009]

- www.asianaustin.com/news/show/69 [Last accessed: Jul. 2009]

FOOTNOTES:

- Air Force Times, December 1998

- FAB-100 Commemorative Album, 1945-1997 ad infinitum, by S. L. Wang

- Air Force Times, December 21, 1998

- Austin American-Statesman, July 19, 1946

© Zak Keith, 2009